Oregon is a great place for birdwatching, with its diverse landscapes and rich birdlife. In this post, we’ll take a look at some of the most common backyard birds in Oregon.

These birds are easy to spot and can be enjoyed by both novice and experienced birdwatchers alike.

So if you’re interested in getting into backyard birdwatching, or just want to learn more about Oregon’s feathered residents, read on!

We will go through the backyard birds in the order of the frequency with which they visit bird feeders in Oregon:

| No. | Bird Name | % of feeders visited by the bird |

| 1 | Dark-eyed Junco | 83 |

| 2 | Black-capped Chickadee | 66.6 |

| 3 | Anna’s Hummingbird | 66 |

| 4 | Pine Siskin | 60.8 |

| 5 | House Finch | 58.7 |

| 6 | Spotted Towhee | 56.5 |

| 7 | California Scrub-Jay | 54.9 |

| 8 | Northern Flicker | 51.1 |

| 9 | Song Sparrow | 49.1 |

| 10 | Lesser Goldfinch | 42.9 |

| 11 | Steller’s Jay | 42 |

| 12 | Red-breasted Nuthatch | 40.8 |

| 13 | Bushtit | 37.7 |

| 14 | Downy Woodpecker | 37.2 |

| 15 | Golden-crowned Sparrow | 34.5 |

| 16 | Chestnut-backed Chickadee | 33.7 |

| 17 | Mourning Dove | 32.9 |

| 18 | European Starling | 29.2 |

| 19 | American Robin | 25.6 |

| 20 | American Goldfinch | 25.5 |

| 21 | American Crow | 23.9 |

| 22 | Bewick’s Wren | 20.7 |

| 23 | Townsend’s Warbler | 20.2 |

| 24 | Eurasian Collared-Dove | 19.8 |

| 25 | Varied Thrush | 17.6 |

| 26 | House Sparrow | 16.4 |

| 27 | White-crowned Sparrow | 16.1 |

| 28 | Fox Sparrow | 15.4 |

| 29 | Yellow-rumped Warbler | 15.2 |

| 30 | Ruby-crowned Kinglet | 13.7 |

Read on for much more detailed descriptions and statistics for each of the most common birds in Oregon state!

Contents

Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis) in Oregon

Dark-eyed Juncos are one of the most abundant and widespread forest birds in North America, with populations estimated to be anywhere from 200-630 million. They are part of the New World Sparrows family, Passerellidae. ìDark-eyed Juncoî actually refers to a broad group of birds in the sparrow family, with 16 identified sub-groups that live broadly across North America. Many of these sub-groups were at one point considered different species.

Juncos are small birds, weighing 18-30 g (5/8-1 1/16 oz) with a wingspan of only 15-17 cm. They live in flocks and are generally dark gray or brown, with a pink bill and white outer tail.

Their appearance and colouring vary depending on geographic location. Across Canada and northeast US, you can find ìslate-colouredî populations, and ìwhite-wingedî birds nest in the Black Hills mountains in South Dakota.

ìPink-sidedî juncos can be found in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, and ìRed-backedî populations live in the mountain regions of Arizona and New Mexico. The ìGray-headedí Junco live in the geographic areas between the ìPink-sidedî and ìRed-backedî ranges. Finally, the ìOregonî Junco resides (unsurprisingly) in Oregon! It can be found along the majority of the West coast of North America, from Mexico to Alaska.

Whereas the appearance varies greatly among sub-species, the female Juncos tend to be paler and more brown, almost to the point where they may be confused with tree- or house sparrows.

Where to find the Dark-eyed Junco

They prefer open spaces like backyards, parks, roadsides, fields, and forest. Juncos are ground birds, so look for them hopping between shrubs, low branches, and lawns. The different colour varieties have separate ranges in the summer, but winter migration to new ranges can cause them to flock together.

In the winter, Dark-eyed Juncos migrate south, ranging from southern Canada to northern Mexico, but they tend to avoid Florida. While most Juncos are migratory, some of the populations in the southwest and on the southern Pacific coast may not migrate. Females tend to winter in slightly more southern locations than males.

The Dark-eyes Junco is known casually as ësnowbirdsí due to arriving at birdfeeders during winter snowstorms.

Feeding the Dark-eyed Junco

Seeds make up about 75% of Dark-eyed Juncoís diet, but will also eat insects and berries, particularly during the breeding season. If you want to attract them to your yard, they are very comfortable going to feeders.

You can use a large hopper, a platform feeder and scatter seeds on the ground. They definitely prefer millet to sunflower seeds. You can see them hopping on the ground as they forage.

Breeding & Nest Building

Despite a wide variety in range, the Dark-eyed Junco consistently breeds in forests, preferring coniferous or mixed woodlands on the edges of clearings or other open spaces.

Dark-eyed Juncos breed from May-August, hatching 1-3 broods with 3-6 eggs per brood. Females will choose the nest location and build the nest in 3-7 days. Nests are generally on the ground, in well-hidden locations and are rarely more than 10 feet off the ground. In more populated areas around humans, they sometimes make their nests in buildings, window ledges, light fixtures and hanging flower pots.

Females weave the materials together to form an open cup, which can include twigs, grasses, leaves, moss, ferns, and hair. Juncos donít reuse nests, preferring to build new ones each season. The female incubates the egg, which takes 11-13 days.

The male will protect his nesting territory by singing from a high perch. Both parents will feed the nestling, which leaves the nest 9-13 days after hatching.

Occasionally, a Dark-eyed Junco will mate with a White-throated Sparrow, leading to a hybrid bird that looks like a more gray White-throated Sparrow with white outer tail feathers.

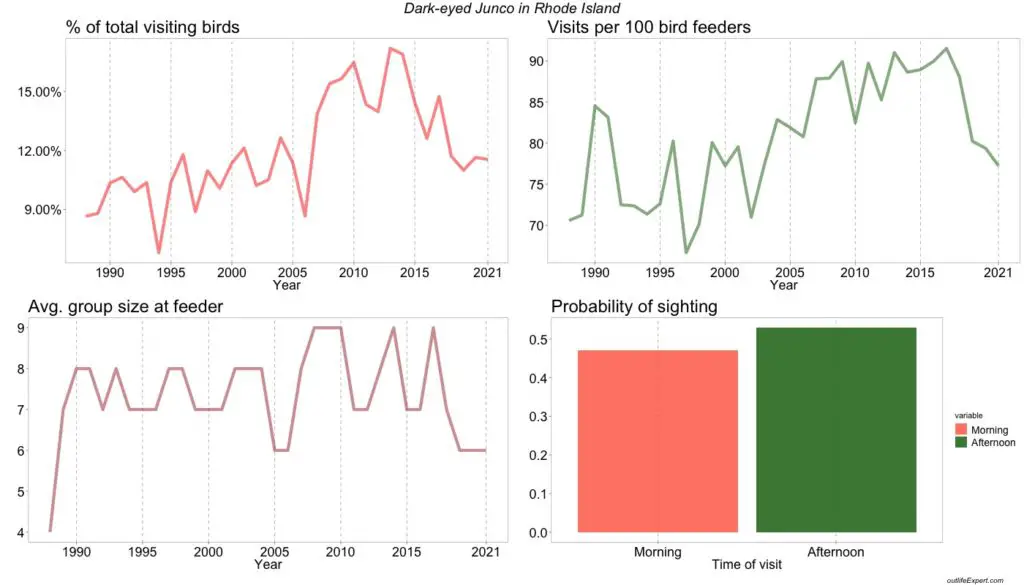

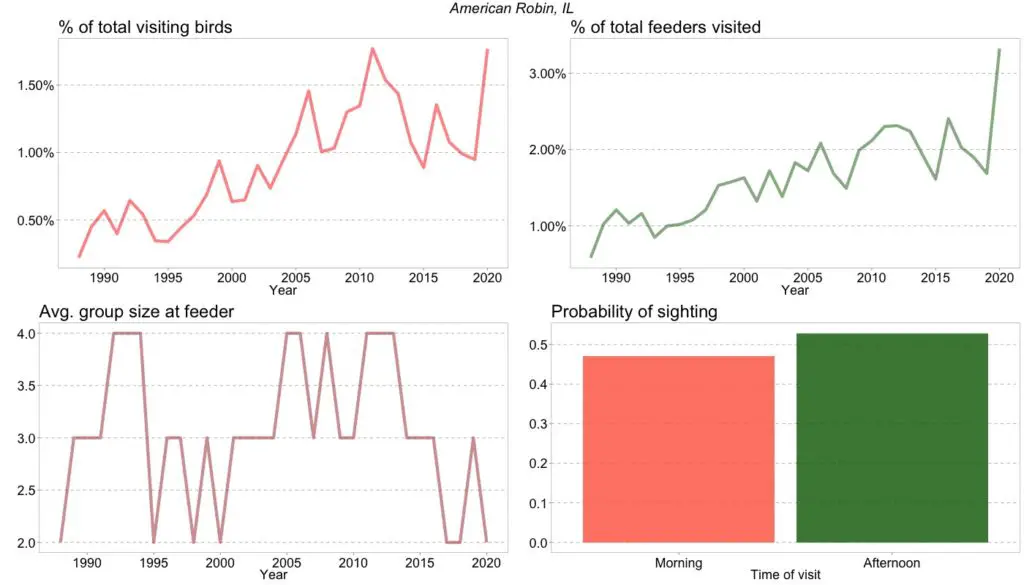

% of total visiting birds: The proportion of the specific bird out of the total number of birds observed bird feeders in this state.

% of total feeders visited: The proportion of feeders (out of all participating feeders in the state each year) where the bird was observed at least once within 2 days.

Avg. group size at feeder: The average number of birds counted simultaneously for each bird feeder observation.

Probability of sighting: The chance of spotting the bird in either morning (before 12 noon) or afternoon (after 12 noon). If both are 0.5 there is an equal chance of spotting the bird in the morning and afternoon.

?

Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) in Oregon

Black-capped Chickadee summary:

Family: Paridae

Occurrence: Canada, mostly Northern US and some central parts.

Diet in the wild: Insects, seeds, berries.

Feeder type preferences:

- Large tube feeder

- Ground feeder

- Suet Cage

- Small hopper feeder

- Large hopper feeder

- Platform feeder

- Window feeder

Feeder food preferences:

- Black Oil Sunflower Seeds

- Hulled Sunflower Seeds

- Safflower

- Mealworms

- Crushed peanuts

- Whole peanuts

- Nyjer seeds

- Suet

Endangered: No.

These curious little birds are quick to discover birdfeeders and habituate to human presence. They can even learn to eat from a personís hand!

In winter they form large flocks mixed with other bird species. They prefer mixed and deciduous forests, especially along the edges. However, they also do well in suburban areas with sufficient tree cover.

Their distribution spans from southern Alaska to Newfoundland, and to the south from Oregon to New York and inland as far south as Colorado and Kansas. They are the state bird of massachusetts and Maine and the provincial bird of New Brunswick.

As birds with a more northerly distribution, they are especially cold tolerant. They survive cold winter nights by seeking cover in thick vegetation or cavities and by going into a hibernation-like state where they reduce their body temperature and metabolic rate to save energy. The presence of bird feeders increases their survival during winter months, especially in the northern parts of their distribution.

Black-capped chickadees belong to the Paridae family which also contains tits, and titmice. They can hybridize with Carolina chickadees or mountain chickadees where their ranges overlap. Other North American chickadees include the grey-headed chickadee, the chestnut-backed chickadee, the boreal chickadee, and the Mexican chickadee.

Identifying the black-capped chickadee

The black-capped chickadee is 5 to 6 inches with grey upper parts, light undersides, rusty flanks, white cheeks, and a black cap and bib. They can make many different sounds, including the distinctive call they were named after: ìchick-a-dee-dee-deeî.

The Carolina chickadee looks similar but has a more southerly range and less white edging along its wing feathers. Even though the Carolina chickadeeís call is different, both birds can learn each otherís song, making it difficult to tell them apart where they co-occur. The mountain chickadee has a black eye stripe and a white brow. The boreal chickadee in Canada has a brown cap, instead of black and the chestnut-backed chickadee, as the name suggests, has a chestnut-colored back.

Mating and favorite foods of the black-capped chickadee

Their breeding season is from late April to June. They nest in nest boxes or cavities in larger garden trees. They will use natural cavities, abandoned Downy woodpecker nests, or excavate their own nest in dead wood. The nest is a cup-shaped structure of moss, bark, and other plant material, lined with animal fur. They can lay one to thirteen white eggs with fine reddish-brown spots.

They have a varied diet, consisting mostly of seeds, fruit, and insects. In summer months, they can be seen catching insects mid-air. Occasionally, they will pick bits of fat and meat from carcasses. They will stash food during autumn and winter and are exceptionally good at remembering the locations.

How to attract the black-capped chickadee to your garden

Black-capped chickadees are easy to attract to gardens. They will enjoy suet, sunflower seeds, peanuts, peanut butter, and mealworms at a birdfeeder.

Place feeders close to vegetation cover. Provide shelter for them with willow, alder, birch, and various shrubs in your garden.

You can plant sunflowers and watch them pick the seeds from the flower heads. They also enjoy the seeds of asters, black-eyed Susans, and coneflowers. Create an insect-friendly garden by providing mulch, dead wood, and indigenous vegetation.

To encourage them to breed, you can put up a nest box with sawdust inside, or a large dead tree stump for them to excavate.

Conservation status and threats

They are listed as least concern since their population is stable. Recently, their western populations have been declining, but, simultaneously, their eastern populations have been increasing. Climate change could cause a northward expansion and a southward contraction of their range. Raptors will prey on adults and squirrels are a threat to their chicks and eggs.

% of total visiting birds: The proportion of the specific bird out of the total number of birds observed bird feeders in this state.

% of total feeders visited: The proportion of feeders (out of all participating feeders in the state each year) where the bird was observed at least once within 2 days.

Avg. group size at feeder: The average number of birds counted simultaneously for each bird feeder observation.

Probability of sighting: The chance of spotting the bird in either morning (before 12 noon) or afternoon (after 12 noon). If both are 0.5 there is an equal chance of spotting the bird in the morning and afternoon.

House Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) in Oregon

Family: Fringillidae (True finches)

Origin: Southwestern US, and Mexico.

Diet in the wild: Weeds, grains, seeds, fruits, insects.

Feeder type preferences:

- Large Hopper

- Small Hopper

- Small tube feeder

- Large tube feeder

- Ground feeder

Feeder food preferences:

- Black Oil Sunflower Seeds

- Hulled Sunflower Seeds

- Safflower

- Nyjer seeds

Endangered: No.

The House Finch is a medium sized finch of the Finch (Fringillidae) family. It is native to the west coast of the USA and parts of Mexico but was brought to the East coast by petshop owners selling them as pets in New York (Long Island) in the 1940s. Although it was not legal to import and sell non-native birds, their quickly gained popularity as pets lead to the spread of the House Finch throughout the remaining states of North and East America.

From the 1960s the House Finch populations expanded from the Northeast towards the west coast to merge with its indigenous population by year 2000. However, mainly due to the House Finchís unusual susceptibility to parasitic diseases, its numbers declined slightly in the 1990s but have since rebounded to record highs.

Identification and confusions

The House Finch is a common feeder bird but may be confused with the Purple Finch or the Cassinís Finch as especially the females are very similar looking. However, there are some subtle but important differences that can help you to distinguish these finches from each other.

Weighing from 16g to 25g the House Finches tend to be slimmer than Purple Finches (20-30g) as well as the Cassinís Finches (25-35g) and the latter two species have less pronounced markings and longer tails. The colouring of the sister species is more diffuse and covers the head and goes down the back all the way to the tails, whereas the House Finch mostly have markings on the neck and a spot just above its tail.

The House Finch also have a red colour similar to that of the Purple Finch and the Cassinís Finch, but the latter two have a darker purple or burgundy colour rather than the brighter strawberry red of the House Finch.

Another important fact that will make it easier for you to pinpoint the House Finch is that the Cassinís Finch is only present in the south-western parts of the US and less associated with gardens and urban areas. The Cassinís Finch is generally rare at bird feeders and only occurs in the west, so if you live in the east or central parts of the US it is much more likely that the red plumaged Finch at your feeder is a House Finch.

Nesting and mating of the House Finch

During the nesting season from March till August, the female quickly builds a small nest from weeds, grasses, and thin branches. It builds the nest in a matter of days and may place it in trees, hanging vegetation or man-made cavities. Contrary to many other common garden birds, the House Finch does not like to build its nest in man-made bird houses.

The courtship of the House Finch is interesting in that it is sometimes selected based on the type of food it presents to its chosen female on their first date. This ritual may have come about due to the role of the male in feeding the female during the entire egg incubation.

What do House Finches eat and how to attract them?

House finches eat grains, seeds, berries, flower buds and are avid consumers of weeds and smaller insects such as aphids. House Finches are one of the few bird species that prefers to feed their nestlings seeds and other plant material instead of the more protein rich insects. The nestlings prefer dandelion seeds so make sure to keep a few dandelions left in your garden if you want to attract the House Finch.

In Hawaii, the House Finch was introduced in the late 19th century where it quickly became known as the ìPapaya birdî. Due to its large intake of papaya instead of the usual seeds and flower buds it would eat elsewhere, the Hawaiian House Finch often had a more yellowish tone compared to the mainland birds.

House Finches are common and very active at bird feeders, and you may use the following seeds to attract the House Finch to your bird feeder:

- Black oil sunflower seeds

- mustard seeds

- millet

- milo

- Cherries

- Apples

- Apricots

You may consider a tube feeder, a hopper feeder, or a Nyjer Feeder to attract the House Finch, however, it is also seen at nectar feeders, where it competes with humming birds for the sweat sap.

It does like to crack open the sunflower seeds and throw the shell on the ground, so make sure to allow for the empty shells to be tossed of easily. So make sure to consider the location of your feeder as shells will collect underneath.

If you really want to make House Finches happy in your garden, you also need a way for them to drink and shower. Especially if the weather is warm, a House Finch may need to drink up to its own body weight in water each day! A bird bath or a shallow pond could work for that purpose.

If, on the contrary, you do not want the House Finch at your feeder, you should make sure to have only nuts, suet, or animal-based feeder material such as mealworms. You should keep dandelions out of your garden and not have any open water around for them to drink or shower.

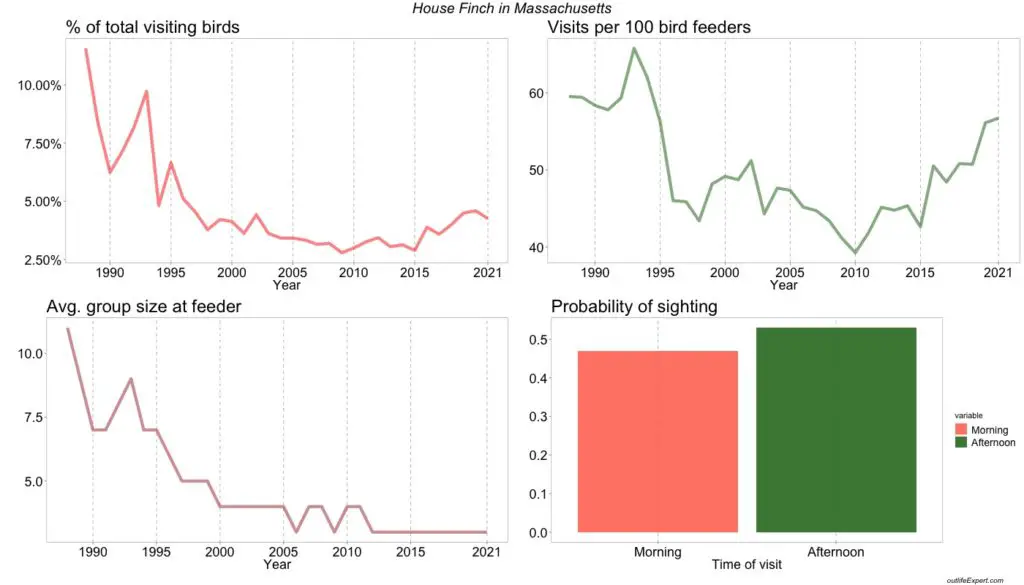

% of total visiting birds: The proportion of the specific bird out of the total number of birds observed bird feeders in this state.

% of total feeders visited: The proportion of feeders (out of all participating feeders in the state each year) where the bird was observed at least once within 2 days.

Avg. group size at feeder: The average number of birds counted simultaneously for each bird feeder observation.

Probability of sighting: The chance of spotting the bird in either morning (before 12 noon) or afternoon (after 12 noon). If both are 0.5 there is an equal chance of spotting the bird in the morning and afternoon.

Looking at prevalence of House Finches at Bird feeders in the United States from 19888 to 2010, we see that the House Finch experienced a drop in the population. This was the case especially eastern and central parts of the US in the early 1990s and was likely due to a high degree of parasite infestations.

The population has later stabilized but the reestablishment has been slow in the United States but is finally on the right track – perhaps because the House Finch collects more in smaller groups (seen from the decreasing flock size in the lower panel). The smaller groups size may have lead to less parasite spread among the birds, but this is not verified.†

Red-Breasted Nuthatch (Sitta canadensis) in Oregon

Family: Sittidae

Occurrence: Throughout United States, and southern/mid parts Canada.

Diet in the wild: Insects in the summer, seeds in the winter.

Feeder type preferences:

- Large tube feeder

- Small tube feeder

- Suet Cage

- Large hopper feeder

- Small hopper feeder

- Platform feeder

Feeder food preferences:

- Suet

- Black Oil Sunflower Seeds

- Hulled Sunflower Seeds

- Mealworms

- Crushed peanuts

- Whole peanuts

Endangered: No.†

The Red-Breasted Nuthatch is a small songbird that is full of energy, very curious and sometimes aggressive towards other birds- particularly in the mating season. The Nuthatches got their name due to their red colored chest and because of the way they fasten nuts into small cracks and peg them open with their bill.

Where does the Red-Breasted Nuthatch come from?

The Red-Breasted Nuthatch is mostly observed at bird feeders in the northern parts of the US and least observations have been made in the South. The populations have fluctuated over time, but mostly for the central and southern parts, and may be due to the increased migration of the Red-Breasted Nuthatch towards the south in years of sparse food supply in the north.

The Red-Breasted Nuthatch can be found in the conifer forests that stretch across North America and most of Canada. It is native to the northern parts of the US but can be seen throughout the country, especially in the mountains of the west, the rolling hills of the eastern states, the Appalachians and the immense forests of Alaska.

How and where to spot the Red-Breasted Nuthatch

These birds measure just 11 cm (4.3 inches) in height with a wingspan of 22 cm (8.6 inches) but they have distinctive markings. They have blue/grey wings and a cinnamon-colored underside, with a white face and throat and a black cap. What is distinctive is the black stripe that passes through their eyes and their long-pointed bill which they use for digging food our of wood and carving holes in the tree trunks where they can build their nests. Their tails are relatively short the female birds are not so brightly colored and their eye stripe is brown rather than black. Both sexes have plumage, but females and young have a duller head and a lighter underside.

The Red-Breasted Nuthatch can be confused with a Black-capped Chickadee, but a second glance will show that they have a longer tail, a smaller bill, and are larger than nuthatches. If you watch them for a while, another tell-tale sign is that they don’t climb up and down tree trunks like nuthatches do looking for insects to eat.

The most likely place you will spot them is in a conifer forest as they are fond of spruce and fir trees. You can spot them in small flocks with chickadees, kinglets and woodpeckers and they can often be seen on tree trunks and branches as they forage for food. The Red-Breasted Nuthatch is monogamous and also remains in its main territory for most of the year, which they guard jealously.

This species is prey to larger birds including hawks, Merlin and spotted owls as well as squirrels and weasels.

The Red-Breasted Nuthatch has a very distinctive call which is a single note repeated several times that has been likened to a tin trumpet!

Habitat and mating of the Red-Breasted Nuthatch

The Red-Breasted Nuthatch loves pine trees and when it comes to nesting time, these birds use their sharp bills to carve out a hollow in the trunk of a pine tree. They build their nest in the hollow by lining it with grass and they then add a layer of feathers for comfort. It is not unusual for the Red-Breasted Nuthatch to steal nesting material from other birdsí nests.

The male also smears pine resin around the entrance to the nest for protection from predators and the female smears pine resin in the nest itself. The birds have just one brood each year, usually in May-July when the female usually lays 5-7 eggs. At this time, the male will be particularly aggressive and chase other birds away from his nest.

The Nuthatches that live in more northern areas often migrate south in September/October if they feel there are not adequate supplies of cone seeds in the forest. If they do stay put and the temperature drops significantly, they will roost communally in a hole in an evergreen tree to try and keep warm. There can be as many as 100 birds in the roost.

What does the Red-Breasted Nuthatch eat and how do I attract it?

The nuthatch uses its long sharp bill to probe in bark to find beetle grubs and insect larvae. In the winter months when these foods are scarce, the Nuthatch eats seeds. Nuthatches are a bit shy at backyard bird feeders, but will gladly visit if there is suet, sunflower seeds, or peanuts on the menu.

Red-Breasted Nuthatches are not considered endangered at all and in the last five years their general numbers throughout the US have been steadily increasing.

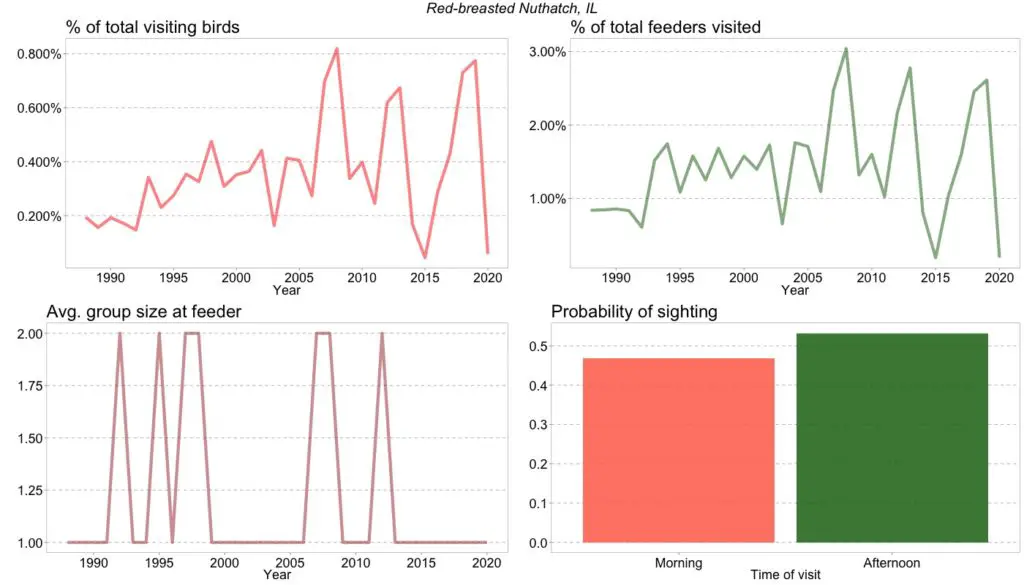

% of total visiting birds: The proportion of the specific bird out of the total number of birds observed bird feeders in this state.

% of total feeders visited: The proportion of feeders (out of all participating feeders in the state each year) where the bird was observed at least once within 2 days.

Avg. group size at feeder: The average number of birds counted simultaneously for each bird feeder observation.

Probability of sighting: The chance of spotting the bird in either morning (before 12 noon) or afternoon (after 12 noon). If both are 0.5 there is an equal chance of spotting the bird in the morning and afternoon.

Downy Woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) in Oregon

Downy Woodpecker summary:

Family: Picidae (woodpeckers)

Origin: Southeastern US.

Diet in the wild: Insects, seeds, berries.

Feeder type preference:

- Large Hopper

- Platform feeder

- Suet Cage

- Small Hopper

Feeder food preferences:

- Black Oil Sunflower Seeds

- Hulled Sunflower Seeds

- Safflower

- Peanuts

- Crushed peanuts

- Mealworms

- Suet

Endangered: No.

The Downy Woodpecker is the smallest and most recognizable of the North American woodpeckers in the Picidae family. It is native to North America, spanning a huge range from the East to West Coast, as far north as Alaska and into the southern US. It avoids the southwestern US as the climate is too arid and does generally not migrate much in winter Except in the very northern parts.

Identification & Confusion with the Hairy Woodpecker

The Downy Woodpecker is a small woodpecker, weighing around 30g (1 1/16 oz), with a length of 6-7 inches. Downy Woodpeckers have distinctive plumage, with crisp black-and-white markings. They have a black back with a white stripe up the middle, white belly and white outer tail feathers barred. Males have a distinctive red spot at the rear of the crown, while the femaleís crown is only black. They have a short, stubby bill they use to excavate wood.

The Downy Woodpecker is often mistaken for the Hairy Woodpecker, as it has similar black and white markings, with a white stripe on the back. The Hairy woodpecker is bigger, has a much longer bill that is nearly half as along as its head, and only have white outer tail feathers.

Unique Behaviours of the Downy Woodpecker

While Downy Woodpeckers are not songbirds, they do have a unique way of making noise with their beaks. They will drum their beaks against wood or metal to create the loud drumming sound we are familiar with. A common misconception is that the drumming is related to the Downy Woodpeckersí feeding habits or excavation, but they actually make very little noise while foraging or excavating. Downy Woodpeckers drum to find mates and to signal to other woodpeckers that this is their territory.

The Downy Woodpecker will typically stay in the same area after breeding, but will range through different habitats, like suburbs and gardens, looking for food.

Downey woodpeckers participate in some unique behaviours in the winter season. They are the only North American woodpecker that uses the reedbed as a winter habitat. They are also frequently found in mixed-species flocks, alongside chickadees and nuthatches – especially at backyard bird feeders! While Downy Woodpeckers are usually solitary birds, flocking in the winter allows them to spend less time watching for predators, as the flock provides safety in numbers and better opportunities for foraging.

Downy Woodpeckers Nesting and favorite habitats

The Downy Woodpecker can breed in a variety of habitats, including deciduous, mixed deciduous-coniferous forests, suburban woodlands, parks, and areas near rivers. Downy Woodpeckers make their nest in dead trees or branches, which both males and females excavate using their bills, to create a nest hole. They can also nest in man-made objects, such as fenceposts, a nest box mounted on a tree or a pole, or even inside the walls of buildings.

Downy Woodpeckers will often choose deciduous trees or wood infected with fungus, as this softens the wood and makes excavating easier. The entrance holes are round and 1-1.5 inches across, but widens near the bottom to 6-12 inches to fit the eggs and the incubating bird. Excavating the nest takes 1-3 weeks, and they do not add any material to their nest once excavated.

The nesting season runs from May-July, where they may have 1 brood with 3-8 eggs. Both male and female will incubate the egg for about 12 days and fledglings leave the nest after 18-25 days.

What do Downy Woodpeckers eat?

Downy Woodpeckers are foragers, primarily eating insects from the surfaces and crevices of both dead and live trees, including food too small for larger woodpeckers. This includes spiders, ants, caterpillars, beetle larvae that live inside wood, and tree bark. The Downey Woodpecker is a very helpful bird, as it also eats many pests and invasive species, like tent caterpillars, bark beetles, apple borers, and corn earworms. They are also known to eat fruits, seeds, and vegetable matter depending on the seasonal availability.

During winter, the male woodpecker dominates the best foraging spots, like small branches and weed stems, actively keeping females out of these areas. The females are left to forage on tree trunks and larger branches, which are less food dense. A research study demonstrated that when the male Downy Woodpecker is removed, the females move to foraging on the smaller branches.

If you want to attract the Downy Woodpecker, they prefer pick on suet blocks to mimic their natural feeding behaviour. They also like black oil and hulled sunflower seeds, safflower, peanuts, peanut hearts, chunky peanut butter, and mealworms. You can use a suet cage, or feeders like large or small hopper and platform feeders.

You can also find the woodpecker drinking out of oriole and hummingbird feeders, but at feeders the Downy Woodpecker will give way to its larger family member, and lookalike, the Hairy Woodpecker.

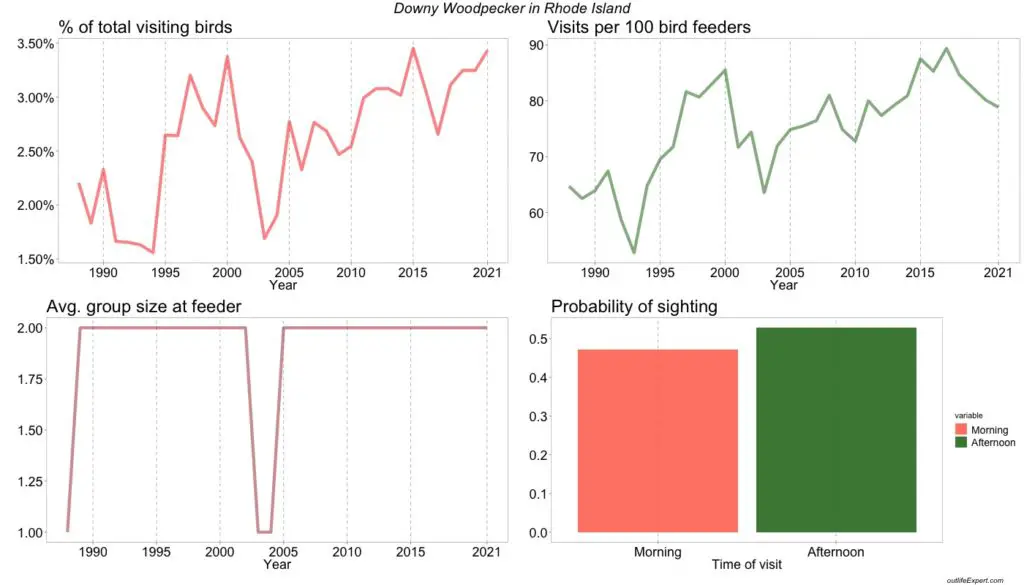

% of total visiting birds: The proportion of the specific bird out of the total number of birds observed bird feeders in this state.

% of total feeders visited: The proportion of feeders (out of all participating feeders in the state each year) where the bird was observed at least once within 2 days.

Avg. group size at feeder: The average number of birds counted simultaneously for each bird feeder observation.

Probability of sighting: The chance of spotting the bird in either morning (before 12 noon) or afternoon (after 12 noon). If both are 0.5 there is an equal chance of spotting the bird in the morning and afternoon.

Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) in Oregon

Mourning Dove summary:

Family: Columbidae

Occurrence: Widely across the United States and Canada. Native to Bermuda.

Diet in the wild: Seeds.

Feeder type preferences:

- Large Hopper

- Platform feeder

- Ground feeder

Feeder food preferences:

- Black Oil Sunflower Seeds

- Hulled Sunflower Seeds

- Safflower

- Cracked Corn

- Crushed peanuts

- Millet

- Oats

- Milo

- Nyjer seeds

Endangered: No.

The mourning dove is one of the most abundant land birds in North America, with an estimated population of 350 million. These birds are known and named for their mournful calls, sometimes confused with owls, and a sharp whistling sound made by their wings when taking off.

Identification of the mourning dove

It is a medium sized dove, (similar to a robin in size) has a long, pointed tail, with a plump body, tiny head, and distinctive dark spots on its wings. It is brownish with a tan head, gray wings with black spots, a black bill, pink feet, and a black dot on the side of the face.

Male doves can be distinguished from females, by a purple iridescence on the neck. The mourning dove may get confused with the Eurasian Collared-dove or the white-winged dove. The Mourning Dove species consists of four sub-specifies, two of which can be found in North America: Z. m. carolinensis, found east of the Mississippi River, and Z. m. marginella in the west.

Habitat and migration of the mourning dove

The Mourning dove has a huge range across North America, meaning there are a variety of breeding and migration patterns depending on where they originate.

Mourning doves who live in the northern end of the range (northern USA, southern Canada) migrate as far south as Mexico. While birds in the central and southern US, might migrate only a few hundred km or not migrate at all.

Mourning doves prefer open spaces, like residential suburbs, rural areas, woodland edges, and fields, but avoids thick forested areas. Most people might recognize the mourning dove from perching on telephone poles and eating from their bird feeder.

Nesting & Breeding of the mourning dove

Mourning doves typically nest from February through October and can have anywhere from 1-6 broods (depending on source) with 2 eggs. These birds mate for life, and work together to build the nest, hatch the eggs, and feed their young.

Over a span of 2-4 days, the male will bring the female materials, which she then weaves into a nest approximately 8 inches across. Males sit on the nest during the day, while the females take the night shift. Eggs incubate for 14 days and nestlings stay for 12-15 days.

Mourning doves will build their nests in a variety of locations – they are not picky and are mostly unbothered by humans.

Typical locations include branches of evergreen, vines, cottonwood, orchard tress and mesquite. In the west, nesting on the ground is common nests can also be found in gutters, abandoned equipment, hanging planters, and eaves.

Nests are made from twigs, pine needles, and grass stems and are described as flimsy in construction. They are unlined and donít have much in the way of insulation for the young. It is quite common for mourning doves to reuse their own nests, or reuse the rests of other species of birds.

Diet of the mourning dove and how to attract it

Mourning Doves are primarily foragers, finding seeds on the ground to eat and they may eat up to 20% of their body weight per day.

Seeds make up 99% of its diet, which can include cultivated grains, peanuts, wild grasses, weeds, herbs, berries and even occasionally snails! The mourning dove typically gets its food quickly, stores it in their crop, and digests it later while roosting.

To attract the mourning dove to your own backyard, we recommend scattering seeds on the ground on platform feeders or in a large hopper feeder.

They prefer black and hulled sunflower seeds, safflower, nyjer, cracked corn, peanut hearts, millet, oats and milo. Since this bird spends so much time on the ground, try and keep prowling animals, like cats, inside.

Encourage nest building by planting dense shrubs or evergreen trees, or even put up a nesting cone in advance of the breeding season.

The mourning dove is a popular game bird

These birds are the most hunted game bird in North America, with around 20 million shot each year. The hunting season varies between regions, but can span from September-January. It is one of the only birds whose hunting season overlaps with its nesting season.

Despite the high volume of hunting, there isnít a high level of concern for conservation according to the Continental Concern Score. There are some differing opinions around the degree to which hunting is impacting this species.

Game managers and conservationists monitor the species population numbers to set hunting limits for the mourning dove. However, some sources say that the breeding population cannot keep up their numbers with the pressure from hunting, especially since nesting doves can be hunted.

A unique side effect of hunting is the lead poisoning of mourning doves in hunting heavy areas. Due to being a ground forager, these birds consume spent lead shot, leading to 1/20 doves eating lead.

Despite hunting of the Mourning Dove, it is still very abundant in American backyards and are frequent visitors of bird feeders.

In Maine, although visiting in fewer numbers per visit, the total number of Mourning Doves are stable throughout Maine backyards.

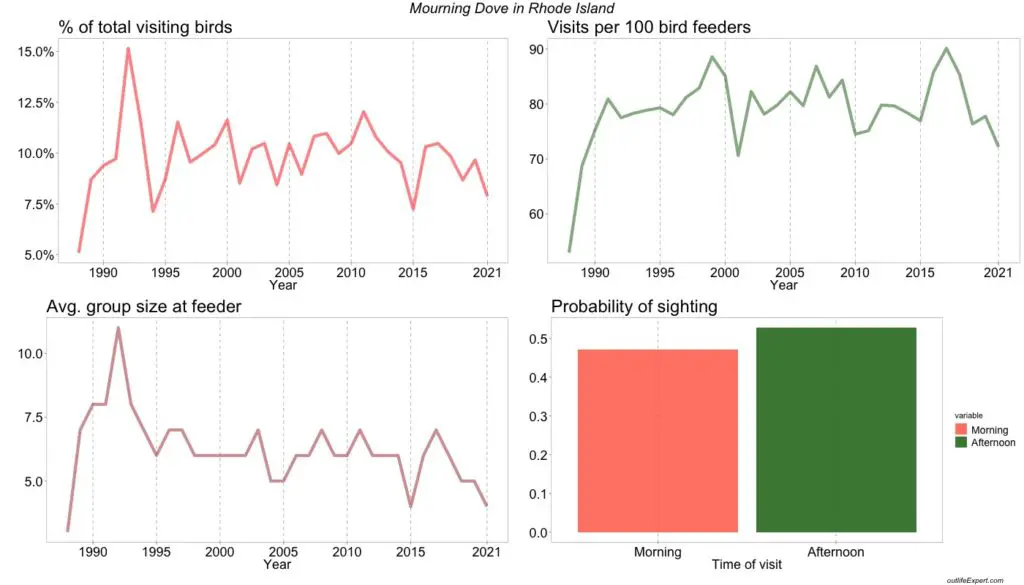

% of total visiting birds: The proportion of the specific bird out of the total number of birds observed bird feeders in this state.

% of total feeders visited: The proportion of feeders (out of all participating feeders in the state each year) where the bird was observed at least once within 2 days.

Avg. group size at feeder: The average number of birds counted simultaneously for each bird feeder observation.

Probability of sighting: The chance of spotting the bird in either morning (before 12 noon) or afternoon (after 12 noon). If both are 0.5 there is an equal chance of spotting the bird in the morning and afternoon.

European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) in Oregon

Family: Sturnidae (starlings)

Occurrence: Throughout North America. Southern parts of Canada.

Diet: Omnivorous. Weeds, berries, seeds, insects.

Feeder type preferences:

- Large tube feeder

- Large hopper feeder

- Platform feeder

- Ground feeder

Feeder food preferences:

- Black Oil Sunflower Seeds

- Hulled Sunflower Seeds

- Safflower

- Crushed peanuts

- Oats

- Fruits

- mealworms

- Suet

- Millet

- Milo

Endangered: No.

The European Starling is also known as the Common Starling and is a very common medium-sized bird that can be found almost everywhere in the United States. It is a very adaptable species so it lives in both the country and in towns and roosts on roofs and telegraph wires as well as trees.

It is however a much-maligned bird as it steals breeding sites from other native birds and is very noisy. They like to form large flocks and they can devastate a farmerís crop and their droppings can carry disease and invasive seeds making the European Starling one of the most destructive species to native wildlife.

Where does European Starling come from?

The European Starling is a non-native species. In the 1890s, 100 birds were brought to the United States and released in Central Park, New York. This was an initiative undertaken by the American Acclimatization Society whose members wanted to introduce many different European species of birds to the United States. They also introduced House Sparrows and Java Finches at the same time. Today, the descendants of those first European Starlings now number in their millions.

How and where to spot the European Starling

European Starlings can be easily spotted in all types of habitat and can often be seen raiding trash cans for food.

The European Starling is 8.5 inches (21 cm) long and has a wingspan measuring 16 inches (41 cm) ñ similar in size to a blackbird. It has a short tail and pink legs. Both sexes look similar and in the summer have a glossy black plumage with a green/purple metallic sheen and yellow beak.

In the winter, its plumage turns to brownish/ black and is often speckled with white and its bill turns brown in color. It is a noisy and aggressive bird and the male makes the most noise with a repertoire that includes whooshing sounds- even in flight- as well as clicking sounds. The European Starling likes to mimic other birds and even man-made sounds like telephones.

Habitat and mating of the European Starling

As well as living in many different areas, the European Starling will nest in any natural or artificial cavity that it has managed to take from another bird. Because the starling is aggressive it will fight hard to win the nesting spot and is not frightened to take on larger birds such as woodpeckers and owls. Their breeding season is March-July and during this time, they will have 1-2 broods of four eggs. Their nest is really untidy. The eggs are pale blue and take two weeks to hatch. The young starlings remain in the nest for just three weeks. The adults feed their young on larvae and insects.

What does the European Starling eat and how do I attract it?

This species is omnivorous and eats a wide variety of foods. They happily visit bird feeders but because of their aggressive nature, they push other birds away so most people donít want to encourage them

The preferred foods of European Starlings include:

- spiders

- cranes

- moths

- mayflies

- bees

- wasps

- spiders

- beetles

- seeds

- fruit

- nectar

- sprouting crops

The European Starling is one of the most numerous birds in the United States, so it is not endangered in any way.

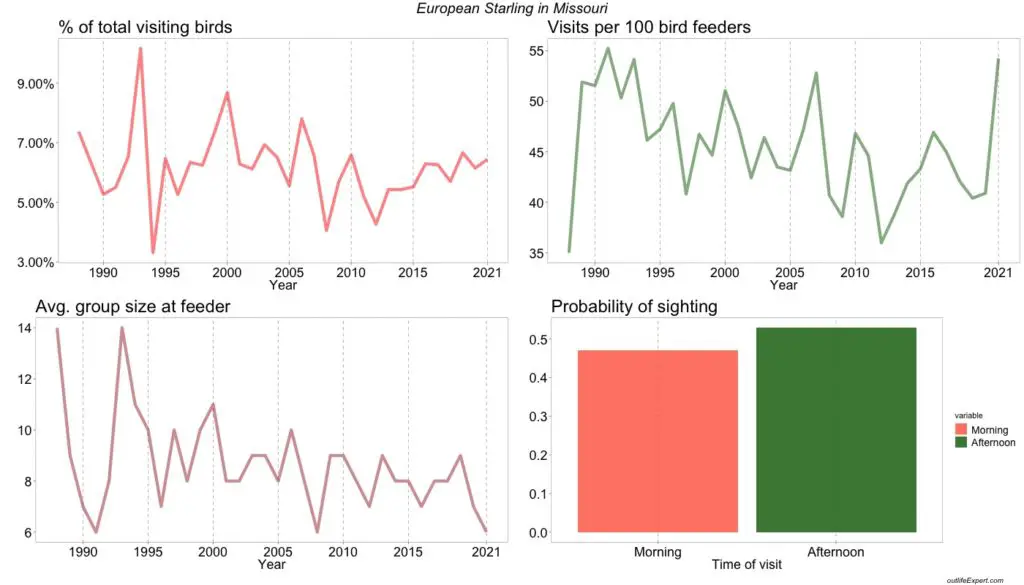

% of total visiting birds: The proportion of the specific bird out of the total number of birds observed bird feeders in this state.

% of total feeders visited: The proportion of feeders (out of all participating feeders in the state each year) where the bird was observed at least once within 2 days.

Avg. group size at feeder: The average number of birds counted simultaneously for each bird feeder observation.

Probability of sighting: The chance of spotting the bird in either morning (before 12 noon) or afternoon (after 12 noon). If both are 0.5 there is an equal chance of spotting the bird in the morning and afternoon.

American Robin (Turdus migratorius) in Oregon

Family: Turdidae

Occurrence: Throughout North America, Canada and Mexico.

Diet: Insects in summer, fruits in winter.

Feeder type preferences:

- Ground feeder

- Platform feeder

Feeder food preferences:

- Crushed peanuts

- Fruits

- mealworms

- Suet

- Hulled Sunflower Seeds

Endangered: No.

The American Robin is a member of the Thrush genus and is one of the most common birds in the United States and can be found in all regions and also in Canada. They will often be seen wandering across a newly-cut garden lawn looking for an earth worm to eat and they are instantly recognizable. There are seven-subspecies of American Robin.

Where does the American Robin come from?

The American Robin is found in all regions ñ as far north as Alaska, but it is a migratory bird and will leave Canada and other colder areas in the fall and head south. Its migration is usually triggered by food levels.

How and where to spot the American Robin

This species of bird can be found in rural areas, open woodland, towns and cities. It measures 8-11 inches in length (20-28 cm) and has a wingspan of 12-16 inches (30-41 cm) The American Robin has a distinctive reddish orange breast, which is a stronger color in the male than female, but otherwise the sexes are very similar. The rest of its body is a grayish brown color with a black cap and it has long legs and pale yellow bill. Around its eyes there are white spots that form a broken ring.

The American Robin is usually the bird to start the dawn chorus and has a high-pitched call but also a very melodic song. It will happily sing all day long and will be one of the last birds to roost in the evening.

Habitat and mating of the American Robin

This Robin is happy to live in a variety of habitats and forms large roosts often of several thousand birds. The roosts are predominantly male Robins as the females stay in the nest caring for the young, but once they have flown the nest, the female will join the roost.

American Robins like to nest in trees and shrubs. They build their nest from tough grasses, twigs and feathers and they then line the nest with softer grasses that they stick in place using wet mud. They have up to three broods each year and are one of the first birds to lay their eggs. There are usually four eggs but often only one of the young birds in each brood will survive to maturity. The young birds are spotted like thrushes. These birds regularly live six years.

What does the American Robin eat and how can you attract it?

The American Robin is a ground forager and loves nothing better than a pile of dead leaves to rummage for insects. It has a wide diet, but during the winter months eats almost solely berries. The American Robin is a frequent visitor to bird feeders and enjoys suet, sunflower seeds, fruit, peanuts, berries ñ and earthworms. If you want to try and attract a breeding pair, it is worth fixing a nesting box on the trunk of a tree.

The preferred foods of American Robin

- earthworms

- insects

- caterpillars

- berries

- fruit

Many people enjoy seeing the first robins of the year as they feel that spring is on its way. Luckily American Robins are one of the most numerous birds in the United States and its numbers are rapidly increasing in Oregon (see graph below)!

% of total visiting birds: The proportion of the specific bird out of the total number of birds observed bird feeders in this state.

% of total feeders visited: The proportion of feeders (out of all participating feeders in the state each year) where the bird was observed at least once within 2 days.

Avg. group size at feeder: The average number of birds counted simultaneously for each bird feeder observation.

Probability of sighting: The chance of spotting the bird in either morning (before 12 noon) or afternoon (after 12 noon). If both are 0.5 there is an equal chance of spotting the bird in the morning and afternoon.

American Goldfinch (Spinus tristis) in Oregon

American Goldfinch summary:

The American Goldfinch is a small, sprightly bird that’s common in Oregon backyards. They have bright yellow plumage and black wings and tails. Goldfinches are usually found in flocks, and can often be seen feeding on sunflower seeds or other garden pests.

Family: Fringillidae

Occurrence: Southern Canada to California in the summer. Also Florida and Mexico in winter.

Diet in the wild: Seeds, insects.

Feeder type preferences:

- Large tube feeder

- Small tube feeder

- Ground feeder

- Large hopper feeder

- Small hopper feeder

- Platform feeder

Feeder food preferences:

- Black Oil Sunflower Seeds

- Hulled Sunflower Seeds

- Nyjer (Thistle) seeds

Endangered: No.

The American goldfinch is a small garden bird commonly found in large flocks throughout the US, southern Canada, and central Mexico. As short-distance migratory birds, they move south during the winter to escape the cold.

During summer they are found from southern Canada to California and North Carolina. During winter, they can be found from Washington to Nova Scotia south into central Mexico. Their natural habitat is open meadows, but they often flock towards bird feeders in suburban areas. They are the official state bird of three US states: Iowa, New Jersey, and Washington.

The American goldfinch belongs to the Fringillidae (finch) family. There are four subspecies: the eastern goldfinch, the pale goldfinch, the northwestern goldfinch, and the willow goldfinch. Other closely related species include the lesser goldfinch, Lawrenceís goldfinch, and the siskins. Despite the similar sounding name, they are not related to the European goldfinch.

Identifying the American goldfinch

The American goldfinch is a 4 to 6-inch, brown to yellow bird with a white undertail. Their wings and tail are black with white markings. In summer, the male is easily distinguishable with his bright yellow plumage and black cap. The female has a pale-yellow underside in the summer months with an olive-colored head and back. In winter, both males and females are olive-brown with a yellowish head. Juveniles are a dull brown with pale yellow undersides. Their call is a chirpy ìtsee-tsi-tsi-tsitî.

Subspecies can be distinguished by their distribution and small variations in coloration and size. The eastern goldfinch is the most common and most eastern subspecies. They occur from Colorado eastwards from southern Canada to central Mexico.

The slightly larger pale goldfinch, as its name suggests, has a paler body, stronger white markings, and a larger black cap in the male. They have a more western range stretching from British Columbia to western Ontario south to Mexico.

The northwestern goldfinch is darker and smaller compared to the other subspecies. They occur along the coastal slope of the Cascade Mountains from southern British Columbia to central California. The willow goldfinch has a browner winter plumage, and in summer, males have a smaller black cap. They are found to the west of the Sierra Nevada range in California southwards into Baja California.

The male lesser goldfinch could be confused with the male American goldfinch but their cheeks and back are olive to black instead of yellow and the black crown of the male covers its entire head. In both males and females, the lesser goldfinch has a yellow undertail, instead of white. The Lawrenceís goldfinch male has a black face and yellow breast, but the rest of its body is grey. Females of Lawrenceís goldfinch have a grey head and back, whereas the American goldfinch has a yellow head and olive back.

Breeding and feeding of Goldfinches

The American goldfinchís diet consists entirely of seeds. Their breeding season starts in June, when seeds are in greatest supply. Monogamous pairs nest in trees or shrubs. Their nest is an open cup of three inches, woven from plant fibers, bound by spiderwebs and caterpillar silk, and lined with plant down. They will lay four to six eggs, each less than an inch long, pale bluish white, with occasional brown spots.

Attracting the American goldfinch to your backyard

To attract the American goldfinch, you can put out various seeds (especially sunflower and nyjer seeds), and beet greens. Use a feeder designed for smaller birds, because large birds at the feeder could discourage the American goldfinch. During the breeding season, you can put out 100% cotton for them as nesting material. Plant indigenous grasses, sunflowers, thistles, dandelions, coneflowers, milkweed, zinnias, and large trees in your garden. A birdbath or water feature would provide an additional attraction.

Is the american goldfinch endangered?

The American goldfinch is listed as least concern since its population is generally increasing across the United States. However, climate change could cause southern contractions in their distribution with local extinctions in various states, due to the increased risks of heatwaves and heavy rainfall endangering their eggs and chicks.

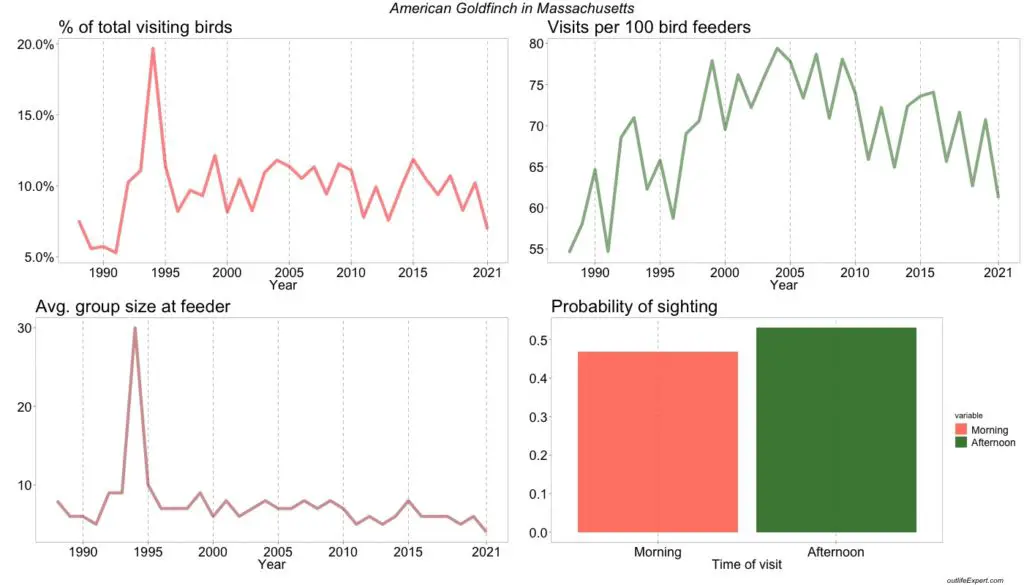

% of total visiting birds: The proportion of the specific bird out of the total number of birds observed bird feeders in this state.

% of total feeders visited: The proportion of feeders (out of all participating feeders in the state each year) where the bird was observed at least once within 2 days.

Avg. group size at the feeder: The average number of birds counted simultaneously for each bird feeder observation.

Probability of sighting: The chance of spotting the bird in either morning (before 12 noon) or afternoon (after 12 noon). If both are 0.5 there is an equal chance of spotting the bird in the morning and afternoon.

Backyard birds in other states

Are you interested in how the backyard birds in your state compare to other states?

Then check out my other blog posts below:

- Backyard birds of Alabama

- Backyard birds of Colorado

- Backyard birds of Delaware

- Backyard birds of Georgia

- Backyard birds of Hawaii

- Backyard birds of Illinois

- Backyard birds of Iowa

- Backyard birds of Kentucky

- Backyard birds of Louisiana

- Backyard birds of Maryland

- Backyard birds of Massachusetts

- Backyard birds of Missouri

- Backyard birds of Nebraska

- Backyard birds of New York

- Backyard birds of North Carolina

- Backyard birds of Oklahoma

- Backyard birds of Rhode Island

- Backyard birds of South Carolina

- Backyard birds of Tennessee

- Backyard birds of Texas

- Backyard birds of Virginia

- Backyard birds of West Virginia

- Backyard birds of Wisconsin

- Backyard birds of Wyoming

And in Canada:

- Backyard birds of Ontario

- Backyard birds of Prince Edward Island

- Backyard birds of Saskatchewan

- Backyard birds of Quebec

Not on the list? Check out the rest of my posts on backyard birds here!

Maybe you would like to know if the Blue Jay or Cardinal dominates in the bird feeder hierarchy or how birds such as seagulls sleep at night? Or why mourning doves poop so much and whether most birds can poop and fly at the same time!

A lightweight handy pair of binoculars is a must for your backyard bird watching! Check out my recent post on the best small lightweight binoculars for birdwatching etc.

My Favorite Backyard Birding Gear:

- Photographs and identifies birds coming to your bird feeder!

- Notifies you via the app whenever a bird stops by!

- Excellent resolution and battery performance with the 6MP image sensor.

- Connect from anywhere with internet access (watch birds even when you are not at home!)

- Count the birds visiting your feeder and contribute to projects such as FeederWatch!

If you are interested in posters and other wall arts etc. with drawings of all the backyard birds you have just read about, check out my portfolio over at Redbubble:

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the Cornell Lab of Ornithology at Cornell University and the Birds Canada organization as well as all the citizens who have been involved in the FeederWatch project for providing the data of this article. The data I have used to generate the prevalence numbers for this article is provided by the FeederWatch project. The FeederWatch project is an initiative by The Cornell Lab of Ornithology at Cornell University and the Birds Canada organization. The data is collected through an immense crowdsourced citizen science program, where citizens of the United States and Canada are invited to count birds at their bird feeders, identify the species, and report back to the scientists at Cornell University. The birds are counted from November to April and always in two consecutive days including only one area with a bird feeder, typically a piece of the backyard, observed from one vantage point. The two-day watch is then repeated throughout the season. The data is collected each year and is freely available to the public at https://feederwatch.org/.

References

American Museum of Natural History Birds of North America. DK; Revised edition (September 6, 2016). ISBN: 978-1465443991

National Geographic Backyard Guide to the Birds of North America, 2nd Edition. National Geographic; 2nd edition (October 15, 2019)

Birds of North America. National Audubon Society. (Knopf April 6, 2021). ISBN: 978-0525655671