Corals, along with sponges, are members of the Phylum Porifera, which literally means ‘pore-bearing’. This name refers to the pores that allow gas exchange (similar to fish gills) and for the release of waste products.

Coral are omnivorous animals that play an important role in the food web of the reef ecosystem. They are secondary consumers, meaning that they eat animals but they also eat plants and detritus so they do contribute somewhat to the decomposition of organic matter in the oceans. They are not producers, but they do have an interesting relationship with algae!

Coral capture plankton like algae and microscopic animals as well as small particles of organic matter from the water by effectively filtering the water.

This diet helps them to supplement the nutrients they receive from their symbiotic dinoflagellate algae partners that also provide them with energy in exchange for giving the algae a place to live!

Like sponges and sea squirts, corals are colonial animals, often building massive structures, some of which are even visible above water, but they do need water to survive.

Contents

Are Corals Producers, Consumers or Decomposers?

Corals are fascinating organisms that play a crucial role in marine ecosystems. In order to understand their ecological niche and their role as producers, consumers, or decomposers, it is important to delve into the complex symbiotic relationship between corals and their photosynthetic algae known as zooxanthellae.

Corals themselves are generally classified as consumers. They belong to the phylum Cnidaria, which includes other animals like jellyfish and sea anemones. As consumers, corals obtain their energy and nutrients by feeding on other organisms.

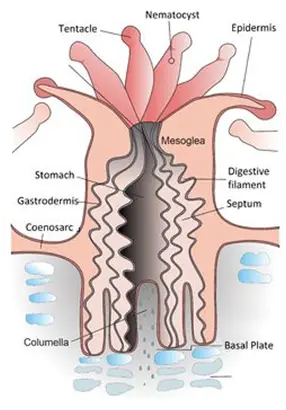

They possess specialized cells called nematocysts that allow them to capture and immobilize small prey, such as plankton, that drift near their tentacles. The prey is then ingested and broken down within their gastrovascular cavity, where digestion takes place.

However, the relationship between corals and their symbiotic zooxanthellae adds another layer to their ecological role. Zooxanthellae are single-celled algae that reside within the coral’s tissues. These algae possess chlorophyll and are capable of photosynthesis, converting sunlight into chemical energy. This process produces organic compounds, including glucose, which can be utilized by the coral.

The coral provides a protected environment and necessary nutrients for the zooxanthellae, while the algae, in turn, provide the coral with essential nutrients through photosynthesis. The symbiotic relationship between the coral and zooxanthellae is highly beneficial for both parties.

The coral obtains a significant portion of its energy requirements from the photosynthetic activity of the algae, enabling it to survive and grow in nutrient-poor waters. It is estimated that corals can derive up to 90% of their energy needs through this symbiotic relationship.

Therefore, while corals themselves are consumers, they have a unique association with photosynthetic algae that act as primary producers. The zooxanthellae within the coral tissues produce organic compounds through photosynthesis, which are then utilized by the coral. This mutualistic relationship is vital for the survival and growth of coral reefs, as it provides the corals with a substantial energy source.

It is important to note that this relationship is delicate and susceptible to environmental stressors. Factors such as increased water temperature, pollution, and ocean acidification can lead to the expulsion or loss of zooxanthellae from corals, a process known as coral bleaching.

When corals experience prolonged stress, they may expel their zooxanthellae, resulting in a loss of their primary energy source and potentially leading to their death.

In conclusion, corals are primarily consumers, obtaining their energy and nutrients by feeding on other organisms. However, their unique symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae allows them to benefit from the photosynthetic activity of these algae, making corals reliant on the energy produced by the algae.

Thus, corals can be considered both consumers and indirect beneficiaries of the primary production carried out by their symbiotic zooxanthellae.

Only plants as well as some bacteria and protozoa are producers.

Structure and Diet of Corals

Corals are small, sessile, non-moving animals. They are colonies composed of individual polyps, which can reproduce asexually or sexually, depending upon species. Polyps are mobile and are responsible for capturing prey and secreting digestive enzymes, which break down the captured prey.

The digested food is then transported across the coral surface, where it can be efficiently captured by the gastrozooid, a gastropod-like opening that leads to the pharynx (feeding organ).

The pharynx then transfers the food through the food conduit, which delivers it to the stomach – yes corals have stomachs!

The stomach then secretes enzymes that further break down the food, which is finally passed into the intestine (food storage area), where the nutrients can be absorbed.

Corals have an important symbiotic relationship with algae called zooxanthellae. These are a type of dinoflagellates that are actually small photosynthetic animal-like protists! But they are not quite animals nor plants just like Euglena are.

The zooxanthellae live inside the coral tissue and provide the coral with nutrients through photosynthesis. And they also give the corals their beautiful colors!

In return, the coral provides the zooxanthellae with some nutrients, a safe place to live, and access to sunlight. This symbiotic relationship is essential for the survival of both species.

Why are corals important for the marine ecosystem?

Corals are important animals in the ecosystem because they provide a home for many other creatures, help to keep the water clean, and provide food for many other animals.

Coral reefs are some of the most diverse ecosystems in the world. They are home to thousands of different species of fish, invertebrates, and other marine life. Without coral, these animals would have nowhere to live and would eventually die off.

Corals also help to keep the water clean by filtering out harmful pollutants and providing a safe place for fish to lay their eggs. Many fish species depend on coral reefs for their survival.

Finally, corals provide food and hiding places for many other animals in the ecosystem. Herbivorous fish graze on algae that grow on the coral reefs, while carnivorous fish eat smaller fish that live among the corals.

If there were no coral in the ecosystem, these animals would not have anything to eat and would eventually starve to death.

Are Corals Carnivores, Herbivores or Omnivores?

Corals are omnivores. They eat both plants and animals. Corals are not considered herbivores because plant matter makes up a very small portion of their diet. Corals eat microscopic algae, plankton and planktonic invertebrates (animals).

However, corals are not classified as carnivores, herbivores, or omnivores in the same way that other animals are.

Corals are actually marine invertebrates belonging to the phylum Cnidaria, which includes organisms like sea anemones, jellyfish, and hydroids. Unlike animals with complex organ systems, corals are colonial organisms that consist of thousands of individual polyps.

The primary source of nutrition for corals is not derived from consuming other organisms, as carnivores do, or solely from plant matter, as herbivores do.

Instead, corals are considered to be symbiotic organisms that engage in a mutually beneficial relationship with photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae. These algae live within the tissues of corals and provide them with a significant portion of their energy requirements.

The relationship between corals and zooxanthellae is known as mutualistic symbiosis. The algae receive protection and access to light provided by the coral’s calcium carbonate exoskeleton, while the coral benefits from the products of photosynthesis performed by the algae. The photosynthetic process converts sunlight into energy-rich compounds, including sugars, which are then transferred to the coral host. This symbiotic relationship is crucial for the growth and survival of most coral species.

While the majority of a coral’s energy needs are met through the symbiosis with zooxanthellae, corals also engage in additional feeding mechanisms to supplement their nutritional intake. Corals possess specialized cells called nematocysts, which are used for capturing and immobilizing tiny prey items such as zooplankton. However, the capture and consumption of these organisms are considered secondary and not the primary source of nutrition for the coral.

Furthermore, corals possess tentacles armed with stinging cells called cnidocytes, which contain nematocysts. These stinging cells are primarily used as a defensive mechanism to ward off potential threats or predators and to prevent other corals from encroaching on their space. They are not primarily intended for capturing food.

In summary, corals are not strictly classified as carnivores, herbivores, or omnivores. They primarily obtain energy through a mutualistic relationship with photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae, which provide them with the majority of their nutritional requirements.

While corals can capture and consume small prey items, such feeding mechanisms are secondary and supplemental to their reliance on the products of photosynthesis.

Can Corals be Decomposers?

Corals are fascinating organisms that play crucial roles in marine ecosystems. While they are primarily known for their ability to form elaborate reef structures, corals themselves do not act as decomposers. Instead, corals engage in a mutualistic relationship with photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae, which provide the majority of their nutritional needs. However, the reef ecosystem as a whole relies on decomposers to break down organic matter and recycle nutrients.

Corals belong to the phylum Cnidaria and are classified as anthozoans. They are colonial animals composed of thousands to millions of individual polyps, each consisting of a central mouth surrounded by tentacles. Within the polyps, the coral host and the zooxanthellae algae live in a symbiotic relationship. The coral provides a protected environment and inorganic nutrients to the algae, while the algae photosynthesize and provide the coral with organic compounds, primarily glucose.

The photosynthetic activity of zooxanthellae is crucial for the survival and growth of corals. Through photosynthesis, the algae convert sunlight, carbon dioxide, and nutrients into organic matter, primarily in the form of sugars. This energy-rich organic matter is then translocated to the coral host, providing a significant portion of its nutrition. In return, the coral offers a stable habitat and access to sunlight for the zooxanthellae.

While corals heavily rely on their photosynthetic partners, they are not decomposers themselves. Decomposition is the process by which organic matter is broken down into simpler compounds by decomposer organisms, such as bacteria and fungi. These decomposers play a critical role in nutrient recycling within ecosystems. They break down dead organic material, including dead coral tissue and other organic debris, and convert it into inorganic nutrients that can be reused by other organisms.

Within coral reef ecosystems, decomposers are vital for maintaining the overall health and productivity of the system. When corals undergo natural or anthropogenic stresses, such as bleaching events or physical damage, parts of the coral colony may die. Decomposers, including bacteria and fungi, assist in breaking down the dead coral tissue, recycling its nutrients back into the ecosystem. This process helps to maintain the nutrient balance, support the growth of other organisms, and promote the overall resilience of the reef.

In addition to bacterial and fungal decomposers, various other organisms contribute to the decomposition process within coral reefs. For example, detritivores such as certain species of worms, sea cucumbers, and crustaceans, feed on decaying organic matter, aiding in its breakdown. These organisms play important roles as part of the reef’s food web and nutrient cycling.

It is worth noting that while corals themselves are not decomposers, they do have certain mechanisms to remove waste products and maintain their environment. Corals possess mucus-producing cells that release a protective layer of mucus. This mucus can trap particulate matter, including organic debris, detritus, and sediment. The coral’s ciliated cells then move the mucus with the trapped particles away from the polyps, reducing the risk of sedimentation and potential smothering.

In conclusion, corals cannot be considered decomposers themselves. Rather, they rely on a symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae for a significant portion of their nutrition. However, decomposers, including bacteria, fungi, and detritivores, are essential components of coral reef ecosystems. These organisms break down dead coral tissue and organic matter, ensuring the recycling of nutrients and contributing to the overall health and resilience of the reef system.

Where are Corals in the Food Chain?

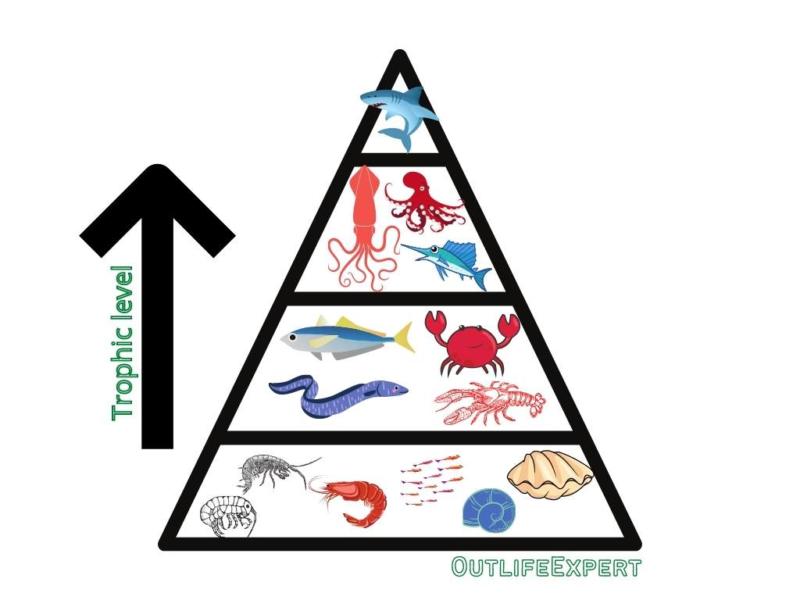

Corals are the second trophic level in the energy pyramid because they are secondary consumers.

Corals play a vital role in the marine food chain, contributing to the overall biodiversity and functioning of coral reef ecosystems. While corals themselves are not directly at the top or bottom of the food chain, they occupy a unique and crucial position within it. To understand their place, let’s delve into the various trophic levels and the interactions involving corals.

The food chain is a hierarchical sequence of organisms, each serving as a source of food for the next. It starts with primary producers, such as plants or algae, which convert sunlight into energy through photosynthesis. In coral reefs, these primary producers primarily include microscopic algae called zooxanthellae that live symbiotically within the coral tissues.

Corals themselves are classified as primary consumers, as they feed on these zooxanthellae. Through photosynthesis, the zooxanthellae produce organic compounds, such as glucose, that provide a substantial portion of the coral’s energy requirements. In return, corals provide a protected environment and necessary nutrients to the zooxanthellae.

However, the primary consumers (corals) also serve as a food source for several other organisms, placing them within the secondary consumer trophic level. Various organisms, such as polychaete worms, sea stars, sea urchins, and some fish species, feed on the living tissue of corals. These organisms are known as coral predators or grazers.

At the next trophic level, there are tertiary consumers, including larger fish species, such as groupers, snappers, and barracudas. These predators feed on the secondary consumers that prey on corals. Additionally, some fish species directly feed on coral polyps or utilize them as shelter, further highlighting the intricate interdependencies within the food chain.

Beyond the trophic levels mentioned above, corals indirectly contribute to the higher trophic levels of the food chain. The complex three-dimensional structure of coral reefs provides critical habitat for a diverse array of marine organisms. These include fish, crustaceans, mollusks, and various invertebrates, which rely on the shelter, breeding grounds, and food sources offered by coral reefs.

The coral reef ecosystem supports an impressive diversity of organisms, and the interactions between these organisms create a complex and interconnected food web. Predators at the top of the food chain, such as sharks and large fish, depend on the abundance and health of the lower trophic levels, including the corals.

Furthermore, the breakdown of coral tissues and the release of organic matter through predation, grazing, and natural decay contribute to the detritus food chain. Detritivores, such as crabs, worms, and bacteria, play a crucial role in breaking down the organic matter derived from corals, recycling nutrients, and facilitating the nutrient flow within the ecosystem.

It is important to note that human activities, such as pollution, overfishing, and climate change, pose significant threats to coral reefs. These threats can disrupt the delicate balance of the food chain by reducing the abundance of corals, altering the composition of predator and prey species, and destabilizing the overall ecosystem dynamics.

In conclusion, corals occupy a unique position in the marine food chain, serving as both primary consumers and prey for a range of organisms. Their interactions with other trophic levels contribute to the biodiversity, stability, and functioning of coral reef ecosystems. Understanding the role of corals in the food chain is essential for recognizing the intricate web of life within coral reef ecosystems and the importance of preserving and protecting these fragile environments.

They eat plants, algae, bacteria and some amounts of microscopic crustaceans (zooplankton) which places them at the 2nd and 3rd trophic levels.

Are Corals Autotrophs or Heterotrophs?

Corals are animals and are therefore heterotrophs because they eat or are dependent on other living organisms for their food. Practically no animals are autotrophic because animals do not get their energy directly from the sun as plants do.

However, corals are a bit different than most animals in this regard!

However, being in symbiosis with algae can make corals (almost) independent of other food sources. If you consider these algae part of the corals they are sort of semi-autotrophs!

What Animals Prey on Corals?

Corals are food for a variety of animals including fish, snails, crabs, barnacles, starfish and marine worms. However, hard corals have a skeleton made from calcium, are not so easy to eat!

Several animals prey on corals, either by directly consuming coral tissue or by feeding on the organisms that live within or around the coral structure. Here are some examples of animals that are known to prey on corals:

- Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (Acanthaster planci): This large and venomous starfish is notorious for its voracious appetite for coral. It feeds by extending its stomach over the coral colony, releasing digestive enzymes, and absorbing the liquefied coral tissue.

- Parrotfish: Some species of parrotfish, such as the stoplight parrotfish (Sparisoma viride) and the humphead parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum), have strong beaks specialized for grazing on coral. They bite off pieces of coral, primarily feeding on the algae and organic matter present in the coral tissues.

- Butterflyfish: Certain species of butterflyfish, like the crown butterflyfish (Chaetodon paucifasciatus), feed on coral polyps. They nip at the coral’s soft tissue and extract small organisms, such as polychaete worms and tiny crustaceans, that live within the coral structure.

- Triggerfish: Some triggerfish species, including the titan triggerfish (Balistoides viridescens), have robust teeth that enable them to take bites out of coral. They primarily target the coral’s hard structure to access the invertebrates hiding within or to create crevices for shelter.

- Filefish: Certain filefish species, such as the black-sided pygmy filefish (Rudarius ercodes), have been observed grazing on coral. They use their specialized mouths to scrape algae and invertebrates off the coral surface, potentially causing damage to the coral tissue in the process.

- Pufferfish: Some pufferfish species, like the saddled pufferfish (Canthigaster valentini), have been observed nipping at corals. While they primarily feed on small invertebrates associated with the coral, their feeding behavior can cause damage to the coral tissue.

- Sea urchins: Certain species of sea urchins, including the rock-boring urchins (Echinometra spp.), feed on coral by using their specialized jaws to scrape and rasp the coral skeleton. They primarily target dead coral or the non-living portions of coral colonies, aiding in the process of bioerosion.

It is important to note that the impact of predation on corals varies depending on factors such as the abundance and health of coral populations, the intensity of predation, and the presence of other ecological stressors. While some predation on corals is a natural part of the ecosystem, certain factors like overpopulation of coral predators or imbalances in predator-prey relationships can lead to significant damage to coral reefs.

Many animals also eat corals when they die. A dead coral will be eaten by small scavengers and bacteria in a matter of months. They also eat their skeleton as a source of minerals!

Conclusion

In this blog post I have looked at the diet of the coral as an animal that is rarely thought about on a day to day basis.

Some of the important take away learnings are:

A coral is actually a small animal living in large colonies that are a vital part of the ecosystem and is often used as a living reef in aquarium.

A coral is an important part of the food chain because it is a secondary consumer.

A coral is a filter feeder and it uses the food that it consumes to build itself and its structure.

A coral is a complex organism that may live in symbiosis with algae – a collaboration that is very interesting to observe.

Unfortunately, many corals are subjected to so-called bleaching, a stress situation that strips them of from their vital algae symbionts:

In this blog post I have looked into the diet of the coral as an animal that is rarely thought about on a day to day basis.

If you are interested in coral, you can find out more about it in my previous post here.